Click any image to enlarge

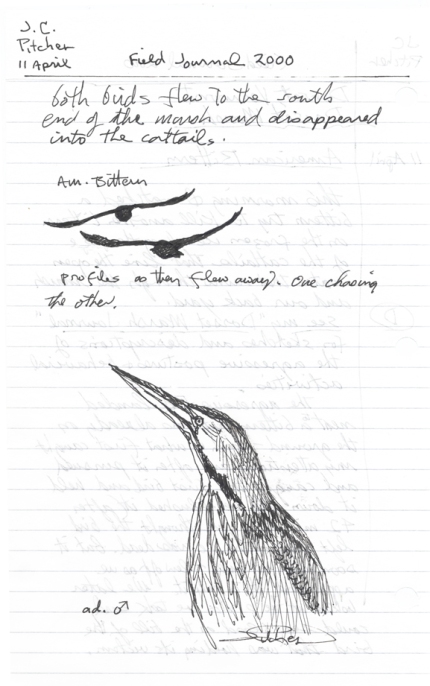

It was April 15th when I stepped outside my studio and finally heard what I have been listening for all week. An airy bubbling belching sound filtered its way through acres of tall dried cattail stalks, across the open marsh waters, past our gallery and into my listening ears. There’s really nothing quit like the courtship calls of the American Bittern. As I stood there listening I took a few minutes, shading my eyes Indian style, to see if I could get a glimpse of it. This bird has a famous reputation for blending into its surroundings, but I knew from years of observations at this marsh, at this time of year when they are calling for a mate, one may actually have a chance to see it in plain site – that is if you have a good pair of ten power binoculars or better yet a spotting scope. I had neither with me at the time, so I didn’t see it. Most people – even birders with the right equipment – don’t always see it. That got me thinking about how lucky I must have been over the past fifteen years when I did see it. Nearly every year since 2000 a bittern has vocally announced its arrival at this marsh in the third week of April, the average return date being the 18th. While I’ve never formally studied this species, over the years through casual observations, I have made numerous journal entries on its courtship and feeding behavior. I’ve sketched its undulating shapes and painted its straw-colored pattern that blends so well with the cattails.

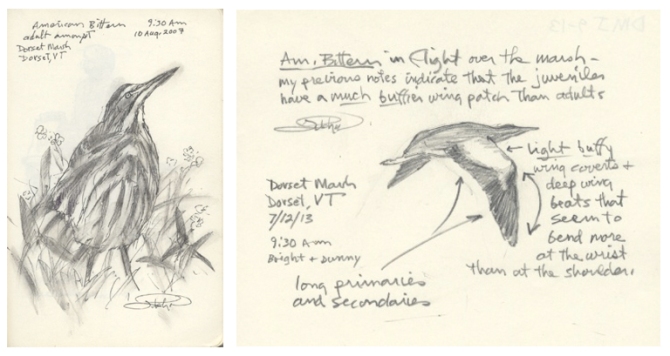

I scanned the following pages of notes and sketches from the different field journals and sketchbooks I was using at the time I made them. They are examples of how constant observations of a species over a period of time can build a “species Profile”. This not only adds to my reference library of field notes and sketches but helps me build a knowledge base about the critters I share this land with. Studying nature through art is also the way I stay connected to life in a soulful way.

All the text and sketches in red ink are from one sighting (I couldn’t find my black pen at the time) and represents a Threat Display and an attempt to kill a rival bird! This is very extreme territorial behavior and to my knowledge has not been recorded before. If you read my scribbled text (sorry about the spelling) you’ll get a pretty good idea what happened. I was in my house when I first noticed two American Bittern circling each other. I grabbed my binoculars to watch what I thought was a mating scene. It soon became apparent there was no “love” intended! The dominate (dark capped) bird grabbed the rival first by its tail, then by its neck as it pinned the rival bird down, strangling it for forty-three minutes! It only let go of its death grip because I decided to intervene by approaching it in my canoe. I knew that was a “no no” – to interrupt a natural event – but curiosity and my anthropomorphic empathy got the best of me.These post card size sketches shows how the dominate bird held its victim down by biting and holding the bird just behind the skull. Probably cutting off blood circulation to the brain. The birds are resting on a thin layer of ice bordering the cattails and open water.

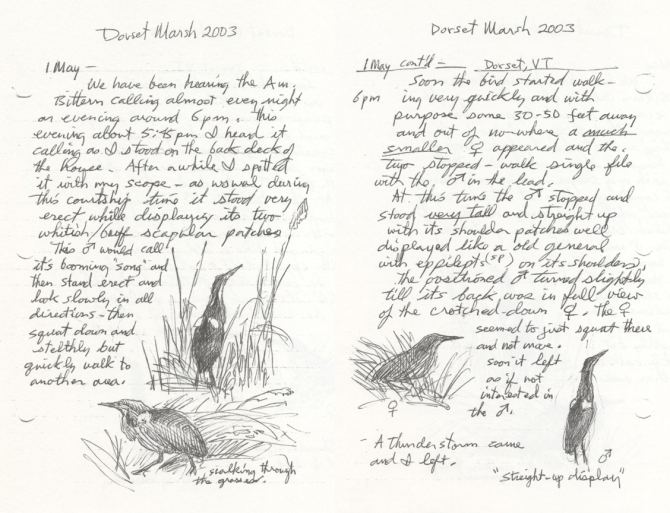

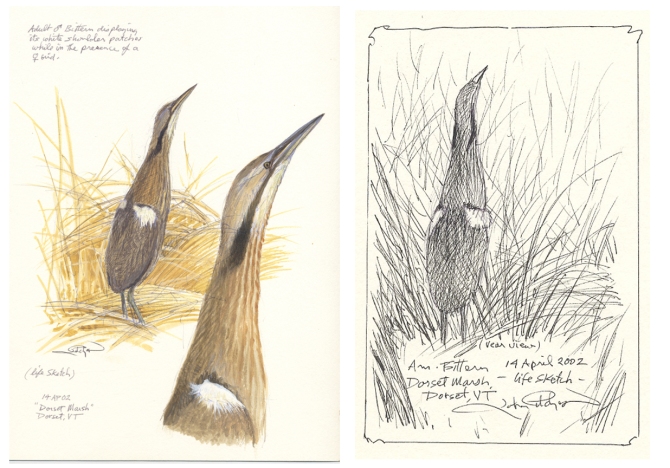

After the attacker let the other bird go it stepped back a ways to watched the victim slowly recuperate, then, suddenly it bolted into the air with a flurry of wings and dangling legs with the attacker in hot pursuit. One of the first steps in the breeding game is to attract a mate by making a low resonating double-burping sound four or five times in a row – all morning long and again in the evening. In order to make this 12 x 9″ page of sketches I first watched the bird through my spotting scope, studying its shape and gestures while it gulped in air then “burped” it back out to make its distinctive call. While lightly sketching the bird in different positions from memory I waited for the bird to start calling again so I could quickly sketch the head positions onto each body. Painting them in with light washes of gouache gave them volume. All five images were made while the bird was still present. If a male sees a female or suspects one is near, it assumes an erect posture and displays white shoulder patches that are normally hidden. The only other time, outside of a Courtship Display, I have seen a bittern display its shoulder patches was during the Threat Display illustrated in the first sketch of this series, but, they were displayed in conjunction with a raised crest, flared neck patches and spread wings. The next two journal pages better explains this bird’s Courtship Display.

If a male sees a female or suspects one is near, it assumes an erect posture and displays white shoulder patches that are normally hidden. The only other time, outside of a Courtship Display, I have seen a bittern display its shoulder patches was during the Threat Display illustrated in the first sketch of this series, but, they were displayed in conjunction with a raised crest, flared neck patches and spread wings. The next two journal pages better explains this bird’s Courtship Display.

Juveniles will retain a big whitish puff of natal crown feathers into mid July – by late July it’s gone.

An adult bittern carries food back to their young by first swallowing it for easy transport, then, stimulated by the young bird’s begging behavior (read the notes below) the adult regurgitates while the young jams its bill down the parents throat to receive the meal.

The shape of the bittern’s pupil is such that it often looks like three joined together. Their eyes are slanted downward, more than most herons and egrets, enabling them to see in front of them while holding its bill straight up in a cryptic posture, also allowing them to hunt using binocular vision.

The bittern seems to be an opportunist, eating most any water-adapted critter. On several occasions I have watched it pull large Bull Frogs out of the Marsh!

To inquire about the availability of any sketch or painting posted please contact me directly.

802 867-5565

ALL IMAGES AND CONTENTS OF THIS SITE COPYRIGHT J. C. PITCHER 2014 – 2015